Obtaining informed consent is a legal and ethical necessity before treating a patient. It derives from the principle of autonomy; one of the 4 pillars of medical ethics: (Autonomy, Beneficence, Non-maleficence and Equality - as described by Beauchamp and Childress1). Touching/treating someone without permission could be considered assault or battery under criminal law and civil law, even if the person was helped by your actions.

For consent to be valid it must be informed consent. For this to be the case it must be:

- Given voluntarily (with no coercion or deceit)

- Given by an individual who has capacity

- Given by an individual who has been fully informed about the issue.

Consent can be written, verbal or non-verbal/implied. A written consent form is not the actual consent itself, but evidence that consent has been given (most forms include sections to record the important aspects of the procedure the patient has been informed of). Implied consent is an action such as offering your arm for blood samples. It can be unreliable as a patient may argue that their actions were misunderstood and they did not actually wish to consent.

Sidaway vs Bethlem Royal Hospital Governors 19852 - a case where a patient was left with paralysis after an operation to relieve a trapped nerve. In the court of appeal, the patient claimed negligence as she had not been informed of the risk of this outcome. The judge rejected the appellants claim as a respectable body of medical opinion agreed that it was not necessary to warn a patient of every risk (Bolam test - see below). The case did however establish in English common law that a doctor has a duty to provide to their patients sufficient information for them to reach a balanced judgement. Patients must be informed how necessary a procedure is, any alternatives, and any common or serious consequences of it. (There remains some debate of what constitutes "common" or "serious".)

If a patient is not properly informed and suffers harm as a result of the procedure, the doctor will be liable for negligence.

The Bolam test is important in cases of negligence. In Bolam vs Friern Barnet Management Committee 1957 a patient suffered severe injuries as a result of receiving Electro Convulsant Therapy without muscle relaxants. The judge ruled taht the doctor had not been negligent and noted that "A doctor is not guilty of negiligence if he has acted in accordance with with a practise accepted as proper by a responsible body of medical men skilled in that particular art." The doctor can still be found to be negligent if common practise is thought to be unreasonable by the court.

Children aged under 16 can be judged to have capacity to consent on a case by case basis if they can fully understand what they are consenting to ('Gillick competent'3). This means that they must understand not only the medical aspect but also the moral and ethical ones too. If a child is not competent to consent, a proxy with parental responsibility can make decisions in the child's best interests (these can however be overruled in court if they are decided not to be in the child's best interests). The parents can consent to a treatment even if their child has refused. The courts can also consent on behalf of a child. The court can overrule a refusal to consent given by the child and the parents and this has happened in several cases where a family of Jehovah's Witnesses have refused consent to a life saving blood transfusion. The courts have also overrulled refusal to give consent to life saving treatment in Gillick competent children. Although this seems to go against individual autonomy the courts tend to take a paternalistic "best interests" approach to children choosing to die.

There is justification in common that information concerning treatment can be withheld if it has been reasonably established that disclosure would cause serious psychological harm to the patient. The Data Protection Act 1998, which states that access to health records can be withheld if it could cause serious physical or mental harm to the patient, may also have some relevance. However, withholding information should not be done lightly and should be well justified and documented.

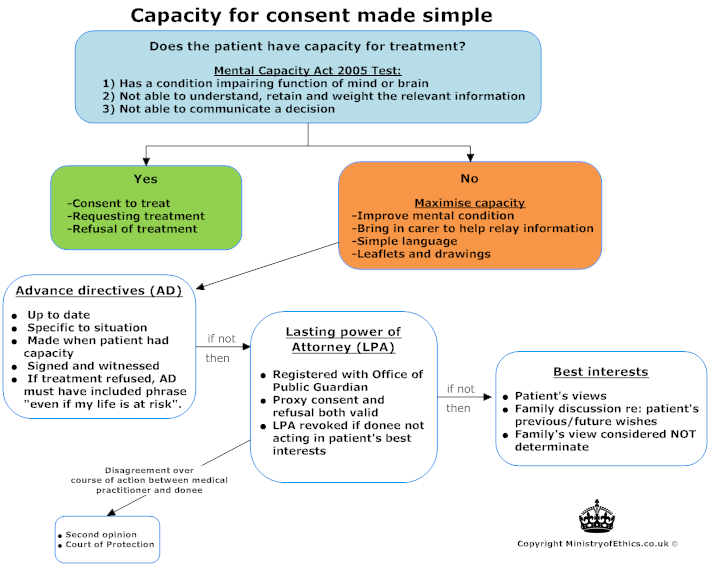

Under the Mental Capacity Act 2005, A patient is deemed to be competent if he can be shown to:

- Comprehend and retain information that has been presented to him in a way that they understand

- Retain that information

- Be able to weigh up that information and use that to make an informed decision

- To communicate his decision (by any means e.g. blinking)

People aged 18 and over are presumed to have capacity unless proven otherwise.

Information must be communicated in a way and at a time that gives the person the best possible chance of taking it in. Lack of capacity needs to be shown for each individual decision that is made; it is not a generalised finding. (i.e. a patient may have capacity to consent to simple prodecures but not to more complicated ones)

If a person lacks capacity then a decision can be taken for them, in their best interests. Establishing a patient's best interests involves taking into account the patient's views and beliefs as well as the views of family and friends, although no one can consent to medical treatment on behalf of an adult lacking capacity. In some cases a patient may have foreseen a situation where medical decisions would need to be made when they themselves lacked capacity. In these instances they may have legally formalised their wishes through either an advanced decision or by nominating someone as having lasting power of attorney. Both legal tools if valid to the current scenario take priority when considering management decisions.

- Advance decisions/living wills -

Only applicable if they are up-to-date and specific to the decision being made. Advance decisions to withhold life-saving treatment such as DNARs must be in writing and signed by the patient and a witness. A decision can be considered invalid if there are unexpected circumstances which it is reasonably believed may have affected the patient's decision. - Lasting Power of Attorney -

Given to an adult (or adults) with capacity by the patient. They need to be officially registered with the Office of the Public Guardian. They enable the nominated adult(s) to make decisions for them. It does not apply to life-saving treatment unless specifically stated. These powers can be revoked by a court if the person is shown not to be acting in the patient's best interests.

The principle of autonomy is paramount here. It is considered to override beneficence in a person with capacity (so they are entitled to make decisions that are not in their best interests). If a person does not have capacity, and has not made any decisions in advance or nominated a person to make decisions for them whilst they still had capacity, then beneficence is the most important principle (so decisions are made in their best interests).

Refusal to consent requires a much higher level of capacity. However if the medical professional believes that the person has capacity then the reasons for refusal can be rational, irrational or even non-existent, then the wishes of the patient should be respected.

There are very few exceptions to the right of refusal:

- Pregnancy: In Re S (1992) the courts ruled to have Caesarean section (a lifesaving procedure for the foetus) despite refusal from the woman on religious grounds. However in 1998 the judge in the case of St George's Healthcare NHS Trust vs S ruled that pregnant women retain the right to refuse treatment even if it is intended to benefit the unborn child.

- Minors: See below and child health section

- Undue influence: If a healthcare professional believes that the patient has been unduly influenced by a relative to refuse a life-saving treatment, then the doctor should ask for guidance from the courts

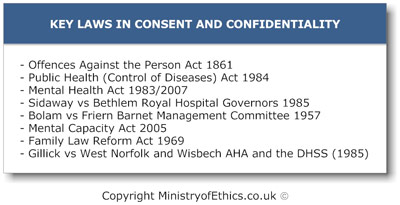

- Offences Against the Person Act 1861

Law relating to crime of assault (battery is a crime under common law) - Public Health (Control of Diseases) Act 1984

Mental Health Act 1983/2007

Law relating to circumstances where a person can be treated without their consent (for serious mental health problems or transmissible diseases that are a public health risk) - Sidaway vs Bethlem Royal Hospital Governors 1985

Bolam vs Friern Barnet Management Committee 1957

Law relating to duty to properly inform about a treatment, and how to establish whether this duty was properly fulfilled - Mental Capacity Act 2005

Law relating to how to decide whether a patient lacks capacity and how decisions are made if they do - Family Law Reform Act 1969

Gillick vs West Norfolk and Wisbech AHA and the DHSS (1985)

Law relating to when children (aged 16/17 and under 16 respectively) have the right to give consent themselves

- Good Medical Practice (2006): "patients have a right to expect that information about them will be held in confidence by their doctors."

Confidentiality is 'the protection of a patient's personal information or personal informed decision from unauthorised parties'. This includes a patient's name and address, not just medical information.

- These notes will aim to take the reader through:

- Confidentiality as a duty of care to patients

- The Consequences of breaches in confidentiality

- The scenarios where confidentiality is most commonly breached.

- When should confidentiality be breached?

- The legal and ethical aspects of the use, transmission, and storage of electronic data. (Data Protection Act 1998)

- Article 8 of the Human Rights Act 1998:

States "Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence" - NHS (Venereal disease) Regulations 1974:

States that GUM clinics can only release confidential information to the patient's GP only with explicit consent from the patient (it cannot be implied) - Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 (1992 amendment):

States that fertility clinics also require explicit consent before allowing disclosure of information to the patient's GP. - Abortion Act 1991:

Abortions must be notified to the Chief Medical Officer - Misuse of Drugs Act (1971):

Known or suspected drug addicts must be notified to the Home Office - Public Health (Infectious Diseases) Regulations 1988:

Certain infectious diseases must be notified to the local authorities (i.e. TB) - Prevention of Terrorism Act 2000:

Any person with information that might prevent an act of terrorism must report it to the police

Minors may wish to conceal their medical history from their parents (i.e. contraception), and if they are Gillick competent then they have a right to confidentiality. The doctor does however have an obligation to try and persuade the minor to inform his parents.

Spouses have no right of information and this includes abortions. The doctor cannot notify the police in cases of martial violence unless they have specific consent from the patient.

- Breaching confidentiality fails to respect patient autonomy.

- Violation of patient confidentiality is a form of betrayal.

- Patients have a right to confidentiality that has frequently been demonstrated in common law and in some specific areas outlined in statute law.

If a patient thinks that a doctor has wrongly breached confidentiality, they are able to pursue their grievance in a number of ways:

- Disciplinary proceedings with the GMC: Can be struck off

- Civil proceedings: Pay patient compensation

- Criminal proceedings

If a doctor is found to be guilty they can be charged in court with breaking the law on confidentiality. As a result they risk being 'struck off' the GMC register (and this has happened to many doctors in recent years). Medical students in turn risk expulsion from their medical school.

- Lifts and Canteens: Discussing information in, small, or crowded places always carries a risk. Caution needs to be taken whenever discussing confidential information.

- A&E departments and Wards: These are areas where there may be many people, especially relatives and friends, who are in close proximity to health-care professionals discussing information about a patient.

- Patient Notes: These are often left in an area with open access, e.g. on the receptionist's desk where other patients and visitors can see them.

- Computers, faxes, and Printers:

- It is very common for patients to see personal information about other patients on faxes or print-outs which have not been filed away promptly. Additionally, when sending sensitive information via a fax machine or printer, it must be ensured that the receiving machine is in a secure place where only those authorized can have access to them.

- An even more frequent scenario is when during the course of a clinic or during the course of a ward round a computer screen bearing a previous patients details becomes visible to the next patient to be seen.

- When the patient gives consent

- Sharing clinically relevant information with other staff to assist in the management of a patient. However if the patient refuses consent to share sensitive information i.e. HIV status to the GP the hospital doctor should respect that wish but should try and encourage the patient to tell his GP. Since the GP would not be placed under risk in normal conditions.

- Sharing information to family members: If patient specifically requests that family members are not told then their wishes should be respected (unless it is a notifiable disease). Rarely, disclosure to 3rd parties may be justified if telling the patient would be injurious to his health (i.e. terminal disease notification)

- Doctors must inform the local officer of communicable disease control if their patient has a notifiable disease e.g. TB, meningitis etc. Full list see the health protection agency guidance3. This is a statutory duty even if the doctor must breach confidentiality.

- Doctors may breach confidentiality if there's a risk of serious harm to others - Common law: W vs. Egdell 1989.

W a psychiatrist released a negative report about a paranoid schizophrenic's (who had previously killed 5 people) mental state - claiming that he was not safe to be released. Egdell's legal team withdrew W's report, but W in the interest of further treatment sent a copy to the hospital in which Egdell was residing. Egdell then claimed a breach of confidentiality by W, which was dismissed by the court. Thereby setting precedent that doctors could breach confidentiality in the interests of public safety.

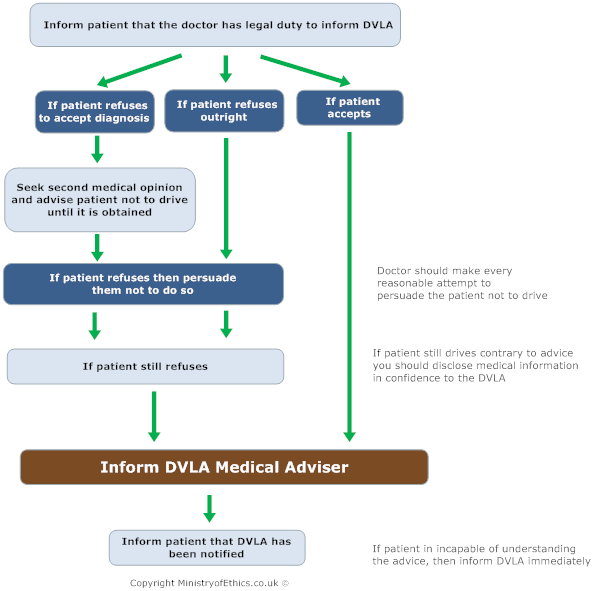

- Disclosure to the DVLA

- Disclosure under the Data Protection Act 1998

- Adverse drug reaction information along with patient details to be given to the MHA (Medicines Control Agency)

- Doctors in private practise may disclose information to tax inspectors but every effort must be made to separate medical and financial information (i.e. bills)

In order to protect the confidentiality of patients in the electronic environment, the GMC has listed some recommendations.

To ensure the protection of confidentiality in an electronic environment the General Medical Council (GMC) recommends that doctors should:

- Make appropriate security arrangements for the storage and transmission of personal information.

- Obtain and record professional advice given prior to connecting to a network.

- Ensure that all equipment, such as computers, are in a secure area.

- Be aware that e-mails can be intercepted.

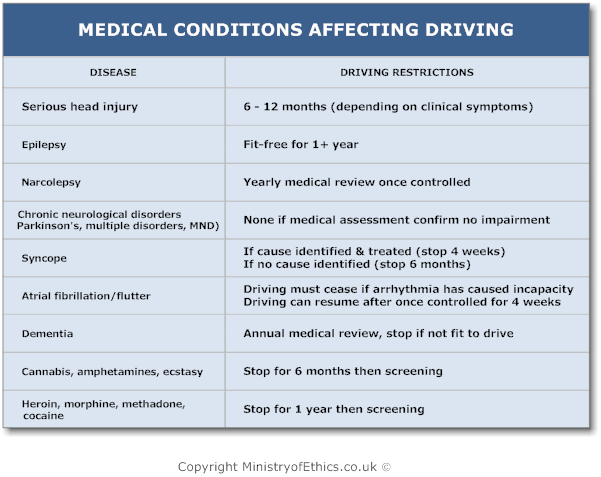

The DVLA driving restrictions is different from cars & motorcycles to LGVs/PCVs. Below are the keys diseases and the restrictions:

Genetic testing is available on the NHS and can be used for the following:

- To confirm a diagnosis of a rare genetic condition, where individuals have a genetic mutation and will nearly always go on to develop the disorder

- To test family members for a known inherited condition that runs within a family

- To establish carrier status in healthy individuals for conditions such as Fragile X - unstable genetic change has the potential to cause disease in future generations even if the individual themselves are not affected

- Carrier status in family members of an affected individual for either an autosomal recessive condition, e.g. cystic fibrosis or autosomal dominant condition, e.g. Huntington's disease, where a positive result means that individual may go on to develop symptoms of the condition later in life

- Carrier of an X-linked condition, e.g. Duchenne muscular dystrophy which may have implications for future pregnancies where the foetus is a boy.

- To test for gene mutations that may increase susceptibility to developing certain conditions, e.g. BRCA1 & BRCA2 increases chances of developing breast and ovarian cancers

- Genetic changes present in certain cancers, e.g leukaemias, which have implications on the treatment and prognosis of the cancer

- Prenatal/neonatal screening for common genetic conditions, e.g. Down's syndrome and phenylketonuria

- Testing functionality of genes, e.g. sickle cell disease

Genetic tests are usually carried out on a sample of blood from which DNA is extracted. The following types of genetic tests are available:

- Gene sequencing - looking mostly at the coding regions of a gene to see if there is a mutation/genetic change causing a disease. This will either be the most common mutations in the population, or if the specific mutation in a family is known then that can be tested for specifically

- Assays to look at the number of copies of a repeat region in coding DNA, e.g. no. of CAG repeats in Huntingtin gene that will cause Huntington's disease - the whole gene is not sequenced

- Cytogenetic analysis - looking at the no. of chromosomes, detecting large deletions/duplications in chromosomes, or whether part of one chromosome has broken off and attached to another chromosome, or may have swapped places with another piece of the same or a different chromosome. Used to detect conditions such as Down's syndrome (Trisomy 21 - an extra copy of chromosome no. 21)

- The UK Genetic Testing Network (UKGTN) act to standardise testing available to ensure that they are accurate and meet quality standards

- All gene tests available have to be approved by the UKGTN for clinical validity and utility and can only be carried out at approved and accredited laboratories

- In order to have a genetic test, patients are usually referred to one of 20 regional genetics centres where a geneticist or genetic counsellor can offer support and counselling, laboratory testing and clinical diagnoses for the patient and their families

- Patients are asked to consent to the sharing of any relevant information with family members which may affect them should a condition be diagnosed

Can genetic testing be carried out on children?

- There are not always simple answers to questions such as these, it depends on the condition parents want testing for

- If it was a condition that manifests relatively early on, e.g. in childhood or adolescence, then identifying affected children may be beneficial in terms of being able to manage the conditions, and potentially prevent complications later on

- In cystic fibrosis is useful to know as these children will be prone to recurrent chest infections; they may have pancreatic insufficiency and need supplements; they may need nutritional supplements to help them grow and develop - but identifying the condition is key to managing it correctly

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is a condition in which individuals develop 100s - 1000s polyps in the colon, which may become cancerous if not monitored and removed

- Prophylactic colectomy may be indicated in some individuals and they are usually monitored with surveillance colonoscopies from adolescence

- Genetic testing is available & clearly it is important to have a definitive diagnosis if this condition is known to exist in a family, so that the child may have the appropriate surveillance and management offered to them

- In such conditions, genetic counselling for the family may help the whole family to understand the condition and implications it will have

- It may or may not be appropriate to tell the child exactly what the problem is depending on how old they are and their ability to comprehend the information. Obviously as the child becomes an adolescent, that may be deemed to be the best time for the child to be seen by a genetic counsellor with their parents to discuss it - this is something that is best decided by the genetic health professionals and parents

- There are circumstances where it would be inappropriate to carry out a genetic test on a child who is unable to consent to the test or understand what the implications are, and in these cases it would be best to wait until the child is older, maybe even 18 years old when they can then make the decision for themselves

- Genetic counsellors or geneticists can be involved at various stages to talk to them about the condition, and if they do want testing to ensure that they are prepared for whatever the results may be

- A good example is genetic testing for Huntington's disease, a late - onset neurodegenerative condition where patients develop chorea and eventually dementia

- In a family where a parent is affected, their child has a 50% chance of developing the condition, and knowing these odds, some patients as adults do not wish to know, so to have had a genetic test as a child can have serious consequences for them, both emotionally and in how they live their life

- Patients should have the right to decide whether or not they want a genetic test, and in this case, a condition for which there is no treatment and the patient can live for 40 years + with no symptoms, it would be difficult to justify such a test in a child who doesn't understand and there is no rush to do the test as in the above examples.

If the mother tests positive for a genetic condition, can they disclose it to their children?

- A positive test for a genetic condition obviously has implications for several family members- siblings, parents and children of the affected individual and extended families also

- It is up to the patient to consent to such information being shared with family members, who can be contacted by genetic services and they may or may not want further information/testing. In this situation, it would technically be down to the parents to make the decision of when they want to disclose it to their children and how

- Genetic counselling services are available for all members of the family, and thus when the time comes, they may seek help from these professionals if they so wish, especially if that child is wanting genetic testing

- The mother would have to judge when they think the child is old enough to understand, and again may depend on the condition and age of onset of symptoms, which if the mother starts showing it may be hard to conceal

- Or, when their offspring are considering starting a family that may be the most appropriate time to bring up the issue

- There is no right or wrong answer, and cultural and religious beliefs may also play a role in how they deal with it. Support is available for those who want it.

If they test positive, can they test their children?

- The answer to this is similar to that of the questions above

- A mother would not be able to test her children unless there is a good reason why the test needs to be carried out as a young child and why it cannot wait until the child is old enough to decide for themselves

- This may be if the condition will affect them earlier on in life and not knowing will deny them possible management of their condition

Is genetic information bound by same principles of confidentiality as other clinical information?

- When a patient comes to the genetics clinic, it is usually a consultation pertaining to health of the immediate family, i.e. the patient and their parents or patient and their offspring

- The patient is asked to consent to relevant information being passed on to siblings or other family members who may be affected, without this clinicians cannot share this information

- Obviously it is a complex issue, and patients are counselled regarding the relevance to other family members as part of the counselling process for genetic test and the implications the results will have on that individual and other family members

- Most will be happy to share information if it will help other members of their family

- This is not always the case, but genetic counsellors are trained to deal with such issues when they arise, but no-one can be forced to share the information

- If they opt to share information, a letter is sent to the family member inviting them to make an appointment if they wish to get more information, and is their choice whether or not to accept

- It is complex as many people are involved sometimes, there are sometimes many conflicts which need to be dealt with in turn, genetics health professionals are the most appropriate to give out information but they also have hour-long appointments in which to deal with such issues

When should the health professional disclose genetic information to family members?

- Genetic information should only be disclosed when they have consent from the patient to do so

- However, the BMA have recommended that there are circumstances where it may be permissible to disclose genetic information without the consent of the patient, as genetic testing is an unusual test. In fact, the GMC currently does not treat medical confidentiality as absolute.

- The BMA (1998, p 72) has listed a number of points that should be considered when deciding to disclose genetic information: why has the patient refused to share the genetic information with their relatives; what is the severity of the condition?; what is the predictability of the condition?; what are the benefits and also what harm will be caused by not disclosing the information?; and if the information is disclosed, what steps will the relatives take to make more informed reproductive decisions or how will the use the information to protect themselves?

- The above applied to competent adults; genetic testing on incompetent adults uses the same principles as performing other medical tests on incompetent persons.

- However, the BMA also stated that it may be justifiable, ethically, to perform genetic tests on incompetent adults, for the benefit of only their relatives. But, by law, this may constitute battery. So, permission to do genetic tests should be sought from the courts, if there is enough time.

Genetic testing is not something to be taken lightly by patients or health professionals as it not only has an impact on the individual, but the whole family - and not everyone welcomes this knowledge!

- Beauchamp and Childress. 1979 The Principles of biomedical ethics.

- Sidaway v. Bethlem Royal Hospital (1984) All Engl Law Rep. Feb 23;[1984] 1:1018-36.

- Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority. 19884 All Engl Law Rep. 1984 Nov 19-Dec 20 (date of decision);1985(1):533-59.

- General Medical Council (UK). Ethical guidance: Confidentiality. October 2009.

http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/confidentiality.asp - Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics, 5th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2001.

- http://www.hpa.org.uk/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/NotificationsOfInfectiousDiseases/ListOfNotifiableDiseases/

- W v. Egdell. All Eng Law Rep. 1989 Nov 9;[1990] 1:835-53.

- Her Majesty's Stationery Office (UK). The Data Protection Act (1998). 1998

http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980029.htm - General Medical Council (UK). Confidentiality: Protecting and Providing Information. September 2000 .

http://www.gmc-uk.org/standards/secret.htm

. About

. About